The sprawling 52-acre Southbridge Landfill in Central Massachusetts has polluted air and water for years, but it may be a zoning violation that finally forces the facility to close down.

Remember how they finally put Al Capone in jail? He was a powerful, well-connected gangster who was willing to intimidate and bully anyone in his way. The feds couldn’t convict him for any of his most egregious offenses – murder, smuggling alcohol, or organized crime – but they finally convicted and imprisoned him for eleven years for tax evasion.

This month, zoning enforcement may have played a similarly surprising role in forcing Casella Waste Systems to remove two stormwater basins at the landfill it operates in Southbridge, Massachusetts. This, in turn, might finally shut down the polluting landfill.

A Long History of Unchecked Risk and Pollution

The Southbridge Landfill has long posed a danger to the communities it borders. Over the years it has repeatedly caught on fire (once for a whole week!), created soil piles that slid into adjacent wetlands, and inspired hundreds if not thousands of complaints about odor, dust, traffic, and trash blowing onto neighboring properties. A truck parked in one of the landfill cells even spontaneously exploded a couple of years ago.

As if that’s not enough, the landfill, which accepts more than 400,000 tons of solid waste each year, has been leaking heavy metals, hazardous airborne compounds, and other contaminants into ground and surface water for decades. Now, about 90 home wells in the neighboring towns of Charlton and Sturbridge are contaminated, too.

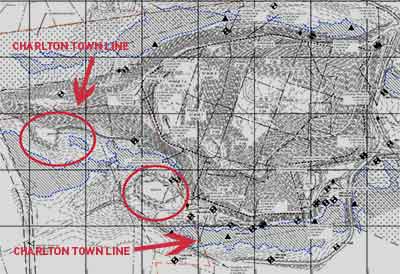

But it isn’t being a dangerous, polluting burden to people and the environment that may ultimately close the Southbridge Landfill. Stormwater catch basins that violate the Town of Charlton zoning code may have finally done the trick. While the bulk of the landfill is located in Southbridge, the facility depends on – and, according to the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, is not allowed to operate without – these stormwater catch basins, which are located on land in Charlton. But that land is not zoned for such a use – and there may be no good place for Casella to move the basins. This is what could finally close the Southbridge Landfill.

The Zoning Law Violation

On May 12, 2016, a group of Charlton citizens notified their Zoning Enforcement Officer that part of the landfill, specifically the two stormwater basins, were located in the town’s agricultural zoning district, which does not permit a landfill use. The citizens asked that the Town of Charlton require Casella to immediately cease all solid waste operations in the town.

After visiting the site and reviewing the law, in November of 2016, Zoning Officer Frederick Lonardo determined that no landfill use, or anything “remotely resembling same under another name” was permitted in an agricultural zoning district under any circumstances. He also reported that, because the manmade basins on the Charlton site are used to manage stormwater at the landfill, they are considered part of the landfill facility. In a letter to Casella, he ordered the company to “immediately cease and desist” use of the basin site for stormwater collection and to operate the site only for uses expressly allowed by the Charlton Zoning Bylaw.

Standing Its Ground

Casella attempted to intimidate the Zoning Board into repealing the cease-and-desist order, but thanks to the sound analysis and clarifying testimony of Zoning Officer Lonardo, the Board of Appeals stayed the course and voted to uphold the order.

Most certainly, Casella will appeal this decision to the courts, during which time the landfill will continue to operate as usual. However, it is very difficult to overturn the decision of a Zoning Board of Appeals, especially if that decision is based on a well-reasoned letter by an experienced zoning officer.

The more interesting question is whether removing the basins from Charlton will cause the entire Southbridge Landfill to close permanently. The state Department of Environmental Protection required the basins in order to improve stormwater management because the landfill was negatively affecting the adjacent wetlands. If the landfill is to continue operating, the basins will have to be moved out of the Town of Charlton, and somehow replaced in Southbridge. Little land is left designated for the facility in Southbridge, so Casella may be forced to divert the stormwater right where they hoped to expand the landfill (though those expansion plans are also currently in question).

Whatever It Takes: Shutting Landfills for Good

This won’t be the first time that a zoning ordinance has thwarted Casella or other waste companies like them. In Hardwick, Massachusetts, Casella was not allowed to expand a local landfill and convert it into a regional landfill because the Town’s zoning, similar to Charlton’s, didn’t allow landfilling in a residential district. Casella was unable to get the Town of Hardwick to re-zone the land from residential to an industrial use that would have allowed the regional landfill. In other instances, cities and towns like Cohasset, Wilmington, and Saugus have passed zoning by-laws limiting the height of landfills in their communities in order to curb unrestricted landfill expansions.

It may not be the most direct method for protecting the community from the health impacts, burdens, and environmental degradation that go hand-in-hand with large landfills. In the end, though, zoning is about limiting and controlling uses that impair the enjoyment of another’s property – uses that make neighbors close their windows to keep out the noise, dust, and smell from a facility like a landfill.

So while many would like to close the Southbridge Landfill because it’s polluting our air, contaminating our water, and destroying the quality of life for its nearest neighbors, let’s salute the citizens, zoning officer, and Zoning Board of Appeals of Charlton. They wouldn’t be bullied or intimidated, and despite Casella’s money or heavy-handed tactics, they upheld the laws of their community.