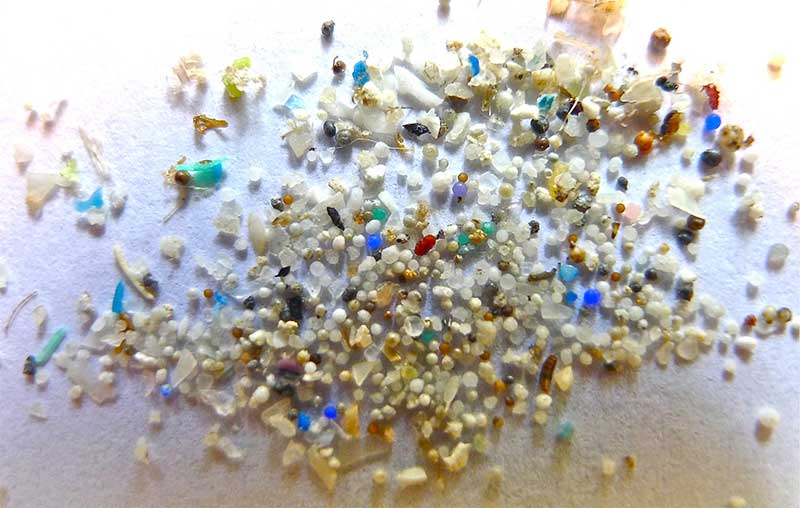

Plastic microbeads in common products such as shower gel and toothpaste are clogging our waters with toxic pollution.

Last week, I gave a presentation on the pollutants that plague Lake Champlain. On one slide I focused on the negative impacts of microbeads – miniature plastic balls so tiny that they slip through wastewater treatment systems and wind up in our lakes (and rivers, streams, and ocean).

Once in the water, microbeads don’t biodegrade over time so we’re stuck with them – and they soak up heavy metals and toxic chemicals. This is especially concerning because many microbeads have been found in the stomachs of fish that humans consume – meaning these small, toxic beads are ending up on our dinner plates.

Microbeads have been used for years in household products such as face soaps, body washes, and toothpastes. So, even if you thought you were doing your part by recycling your plastic bottles and containers, you still may have unwittingly polluted our waterways with plastic simply by using these common products.

An audience member at my presentation was quick to point to the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015 as a significant step forward in addressing plastic pollution. Not being very familiar with this piece of federal legislation, I decided to do a deep dive into how this law will help protect Lake Champlain and other waters across New England. What I discovered, not surprisingly, is that more is needed to safeguard our oceans and lakes.

The Microbead-Free Waters Act bans the manufacture of rinse-off cosmetics that use microbeads. Starting in 2018, companies will also be prohibited from selling these products. This is an important law to cut back on plastic pollution in our waters. Unfortunately, the microbeads we have already introduced to Lake Champlain and waterways around the globe are still there. What’s more, some non rinse-off cosmetics not covered by this law still contain microbeads.

Moreover, microbeads are just one of the many forms of plastic pollution. Some are obvious like bottles and straws. Others are as tiny as microbeads, like microfibers that are shed from synthetic clothing like polyester and nylon when we do our laundry. One way to lower your plastic footprint is to rinse more and wash less – knowing that washing synthetic clothes in the washing machine leads to microfibers in our water.

Ultimately, we can all make a difference by being mindful of the products that we buy and avoiding those that still contain microbeads – while also urging manufacturers to find alternatives to harmful plastics in the products and packaging used so ubitquitously in our society.

We can also work together to change our “throw away” culture. Try to reuse, repair, and recycle before replacing. Plastics have a place in our society, but too often we rely on the easy, replaceable option rather than thinking of the alternatives to our society’s plastic addiction. On its surface, plastic is an economical option for manufacturers and consumers, but the hidden costs to our waterways, our environment, and our health are too high to ignore.