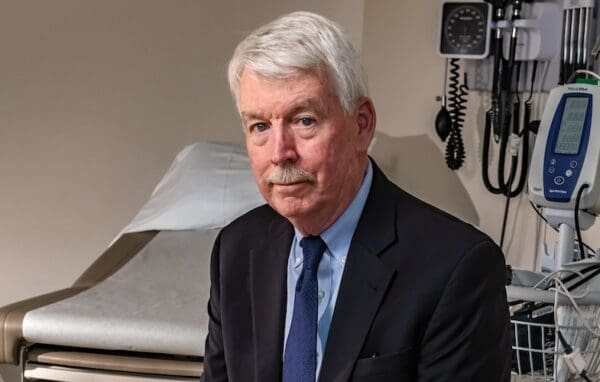

Trailing fishing gear can prevent right whales from feeding, cause injuries, and drain their energy. Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, NOAA Research Permit # 594-1759

Five years ago, I was afraid I’d see North Atlantic right whales go extinct in my lifetime. After a hard-fought agreement to reduce the number of vertical lines used in the lobster fishery, the state of Maine immediately backpedaled on some of its commitments, and the offshore fishery didn’t have the ability to even to make a commitment. These lines that connect buoys on the surface to traps on the sea floor are a leading cause of death for right whales, which can become dangerously entangled in them.

Luckily, there was a path forward: “ropeless” fishing. Instead of placing dangerous vertical lines in the water, ropeless systems use acoustic technologies to bring lobster traps to the surface. These technologies have successfully brought scientific gear off the seafloor for 50 years. Switching away from fishing lines had been discussed for decades, but an actual trial of ropeless systems posed new concerns.

Conservationists worried that if the trial failed, it might set other efforts to improve fishing gear back. Fishermen worried that if the new gear worked, it might be mandated everywhere. The first question, though, was whether the acoustic systems would work at all in challenging fishing conditions.

Ropeless fishing provides right whales with a fighting chance at recovery

We’ve written about the promise of ropeless fishing before. North Atlantic right whales face extinction, in large part because of entanglement in fishing gear. Fishermen don’t intentionally entangle whales – they lose valuable fishing gear and their catch when that happens. But the reality is that U.S. and Canadian commercial fisheries entangle whales far too often. More than 85% of right whales have been entangled at least once.

If a whale doesn’t free itself or die immediately, it may suffer for months, entangled in and dragging heavy fishing gear as it migrates and searches for food. Last year, a young 3-year-old female right whale died after spending half of her short life with a rope from the Maine lobster fishery wrapped around her tail. Because of these chronic entanglements, the species is getting physically smaller, would-be moms are weaker, and fewer calves are born.

Ropeless fishing provides fishermen with tools to fish in currently closed areas

To protect right whales, 62,000 miles of ocean water is seasonally “closed” to fishing with vertical lines. But ropeless fishing (also known as “pop-up” or “on-demand”) offers a solution for fishermen otherwise seasonally closed out of their historical fishing grounds. So, in 2020, the Northeast Fisheries Service (part of NOAA Fisheries) started a Gear Lending Library. Its goal is to provide fishermen with the technical experience they need to resume fishing in the closed areas safely.

The library continues today and offers a growing collection of ropeless systems built with help and donations from environmental and academic organizations. Once a qualifying fisherman completes training on the ropeless system they intend to borrow, they can use the gear and fish in the closed areas. In return, they share valuable data on the gear’s operation and any problems encountered. They can also suggest gear modifications. Fishermen’s feedback has been invaluable to the progress made to date.

Progress to date

Under current fishing regulations, commercial lobstermen must have at least one vertical line connecting traps on the bottom to a surface buoy. This enables them to mark the location of the fishing gear and retrieve their catch. Marking is essential so they can find their gear again and other fishermen can avoid running over it. In 2020, NOAA Fisheries issued a permit exempting fishermen trialing the new gear from these surface marking requirements, and they’ve reissued it every year since then.

Since 2020, the trial has expanded from three boats to more than 50 vessels operating in five states. Nine manufacturers now have more than 500 ropeless systems in the Gear Lending Library. Participants have collected data from retrieving traps just shy of 10,000 times. And the rate of successful retrievals has gone from approximately 65% in 2020 (when COVID-19 presented training challenges) to nearly 90% today.

Is ropeless ready for prime time? Not yet, but soon

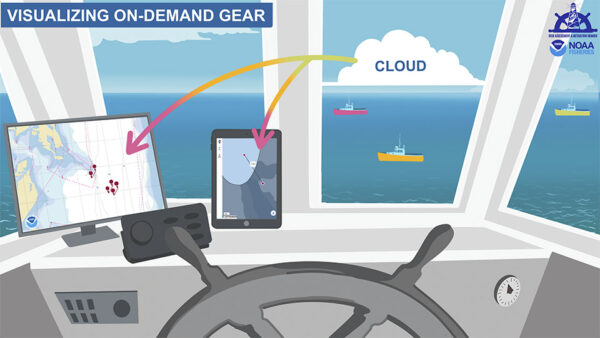

The pitfalls of fishing without a visible marker on the surface remain the biggest challenge to widespread ropeless fishing. To prevent conflicts among people who use the ocean, we need a way for fishermen to track and monitor ropeless gear in real time. Engineers are developing new systems that will do precisely that, mapping all varieties of ropeless systems on a chart plotter.

The cost of ropeless systems is another consideration. Currently, the costs vary widely based on the sophistication of the system and its method of gear marking, but they are all expensive. Costs, however, should decrease as the gear is redesigned for high-volume, low-cost manufacturing, production picks up, and more manufacturers provide additional competition. And because Congress specifically directed NOAA Fisheries to advance innovative fishing gear in the lobster fishery and provided significant funds to do so, we expect the federal government will cover some of these costs.

Finally, there’s still some room for improvement in gear design. Mechanical problems account for most of the 10% of failed attempts to retrieve ropeless gear. Locating the gear in strong currents, bad weather, or at night remains challenging. By working alongside engineers, the fishermen using the gear have significantly improved gear design and operability. With more funding and support, a future where entangling ropes don’t unnecessarily endanger whales is in reach.

What you can do

- Urge your congressional representatives to support funding for ropeless fishing during the annual appropriations process.

- Ask your local seafood restaurant if they carry lobster caught by ropeless gear. If they don’t, ask whether they plan to do so in the future.

- Support CLF as we actively promote innovative technologies that save whales and provide fishermen with the tools they need to keep fishing. With your help, we can work for a future where lobster fishing and whales can co-exist.