Chelsea Flats, a newly opened development in Chelsea, Massachusetts, models how neighborhoods can be transformed from the ground up to support health. Chelsea Flats is one of several projects funded through CLF's Healthy Neighborhoods Equity Fund. Image: Deborah Addis

New England has a housing crisis – and it’s impacting our health.

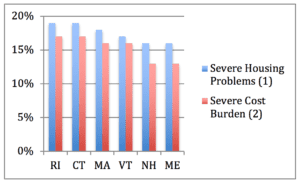

These are the findings of the latest County Health Rankings, a project of the University of Wisconsin and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The study found that housing affordability and quality are significant influencers of health here in New England. More than 15 percent of us in every state struggle with severe housing issues, from overcrowding to high costs. And more than 10 percent of us pay more than half of our income for housing, leaving little left over for food, medical care, and other necessities.

As a member of the Scientific Advisory Group for County Health Rankings, I was pleased that this year’s study looked specifically at the impacts of housing, as the findings support CLF’s own research into the links between housing, neighborhoods, and health.

Launched in 2014, our multi-year Healthy Neighborhoods Study has reinforced the importance of stable housing, particularly for mental health. The study is also generating new insight into how we can design and build neighborhoods that promote good health – such as ensuring that residents are socially supported and can influence the development process in their communities.

We’re using the findings from our research and that of other critical studies, like the County Health Rankings, to shape CLF’s approach to neighborhood development – because a healthy environment encompasses all the places where we live, work, play, and learn.

How Where You Live Affects Your Health

It’s tempting to boil down good health solely to factors like medical care, healthy food, and exercise. But failing to take into account where we live and the stability of our housing means overlooking significant influences on our overall health and well-being.

In another recent study, Dr. Megan Sandel, a pediatrician at Boston Medical Center and CLF’s Healthy Communities Fellow, found that families who fell behind on rent, moved multiple times, or experienced homelessness have significantly higher rates of maternal depression and child lifetime hospitalization.

Conditions inside our homes also matter. Hazards, including lead paint, asbestos, mold, and insects, contribute to poor health and chronic conditions like asthma. In addition, toxic chemicals such as Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) – found in some types of carpeting, paint, and home furnishings – can have severe long-term health impacts.

What’s more, differences between the neighborhoods with the most and least risk from housing instability and environmental hazards are all too often divided along racial lines. For example, nearly one in four Black households spend more than 50 percent of their income on housing – compared to one in ten households nationwide.

These racial divides translate to alarming trends in health. Here in Boston, the average lifespan for a resident of Back Bay, a relatively affluent, mostly white neighborhood, is over 90 years. For a resident of Dudley Square, a predominantly Black neighborhood barely a half mile away, the average lifespan is less than 60 years. Such differences in health between residents of nearby neighborhoods closely follow the outline of redlining maps from the 1930s and 1940s.

What This Means for New England

As the 2019 County Health Rankings show, housing affordability and quality are major challenges in New England. High housing costs hit hardest for low-income families, seniors, and other vulnerable people.

As the 2019 County Health Rankings show, housing affordability and quality are major challenges in New England. High housing costs hit hardest for low-income families, seniors, and other vulnerable people.

In Massachusetts, for example, a household earning minimum wage must work 104 hours per week to afford an average two-bedroom apartment. To afford the same size home in New Hampshire, where the minimum wage is lower, the same household must work 123 hours per week – that’s the equivalent of more than three full-time jobs.

If we zoom in more closely, we also see significant differences between places in the same state. In Massachusetts, 26 percent of people in Dukes County (Martha’s Vineyard) and 25 percent of people in Suffolk County have severe housing problems. That compares to 16 percent in Franklin and Plymouth Counties. These differences in housing, along with other social and environmental conditions, add up to big differences in the health of our communities.

Investing for Health

Such grave differences cannot be remedied through a change in diet, a trip to the gym, or a prescription from the doctor. They are complex, systemic, and neighborhood-wide. And they require an approach to change that brings together the best available evidence, data, and expertise of partners from the private and public sectors and local communities.

That’s why CLF is working to develop innovative investment strategies to attract private capital to worthy housing and economic development projects. In partnership with the Massachusetts Housing Investment Corporation (MHIC), our Healthy Neighborhoods Equity Fund has invested nearly $20 million in seven projects in Eastern Massachusetts. So far, the Fund has supported the creation of more than 550 units of new, energy-efficient housing, with 25 percent of these set aside for low and moderate-income households, and more than 150 new jobs close to public transit.

With the success of the first Fund, we are now working with MHIC to launch a second in Massachusetts later this year. We are also exploring the potential for a similar fund in New Hampshire, where high housing prices are a growing problem for families, communities, and employers.

Turning Knowledge into Action

Your health shouldn’t depend on your zip code. But that’s not the reality for too many of us in New England – or, indeed, the nation as a whole. At CLF, we believe that strategic investments, guided by community priorities and supported by the private and public sectors, are crucial to neighborhood development that promotes and supports health, rather than harms it.

Research studies such as the County Health Rankings and our own Healthy Neighborhoods Study help inform our direction and affirm our results. Our job now is to turn this knowledge into action and create positive, measurable change for people and communities across New England.