I’m riding on a small ferry to an island off the coast of Maine when the captain suddenly slows the boat. He comes over the loudspeaker and speaks in a quiet voice. “On the left of the boat, next to the rocks is an Atlantic Puffin,” he says. Craning our necks, my fellow passengers and I look out on the sparkling blue water and there next to the seaweed covered rocks is a lone puffin bobbing in the water.

Puffins had nearly disappeared from the Gulf of Maine until restoration efforts in the late 1900s successfully restored colonies on the Maine islands. In the past, the greatest threat to puffins was hunting, but now they face a new threat: global climate change. The Gulf of Maine is warming at a faster rate than almost any other ocean ecosystem on Earth. This is bad news for puffins and the 3,000 other marine species who rely on the Gulf waters for food and habitat.

Scientists have been researching ways to slow climate change or at least mitigate its impacts. One new study shows that marine reserves allow ecosystems to adapt and be resilient to the major predicted impacts of climate change: acidification, sea-level rise, more intense storms, shifts in species distribution, and decreased productivity and oxygen availability.

Marine reserves are a type of marine protected area where all activities such as fishing, bottom trawling, fracking, and drilling are prohibited (though minimal amounts of low-impact fishing may still be allowed). Currently, only 3.5 percent of the world’s ocean has some level of protection, with just 1.6 percent fully protected. International scientists agree that by 2030 we need to protect at least 30 percent of the ocean.

According to the study, marine reserves can help combat climate change impacts in a couple of different ways.

Tackling Ocean Acidification

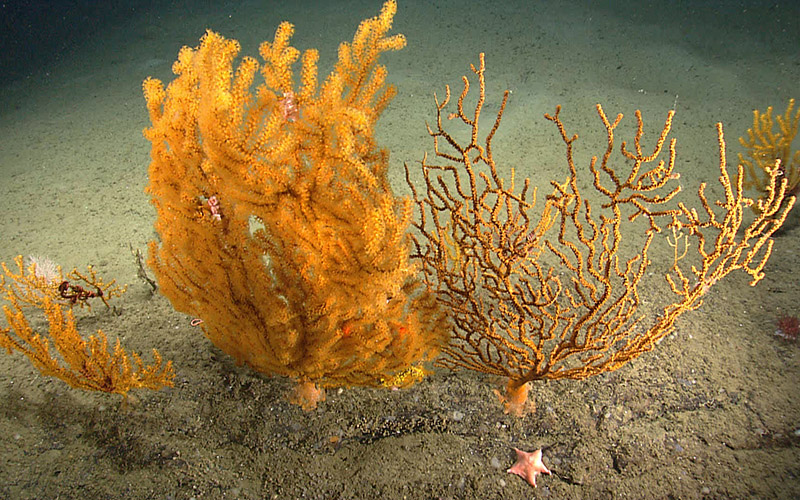

One of the biggest threats to the ocean is acidification. Ocean acidification occurs when excess carbon dioxide enters the water from the air. The carbon dioxide changes the water’s chemistry, making it more acidic. Marine reserves can help the ocean’s resiliency to acidification by capturing and storing carbon in protected wetlands and by creating a stronger buffer against carbon offshore.

Wetlands in particular are able to remove carbon from the atmosphere and store it for hundreds of years. Wetlands can also provide refuge, breeding grounds, and nursery hotspots for many types of organisms. Additionally, protected wetlands can help mitigate two other impacts of climate change – sea level rise and intensification of storms – by providing an important physical buffer between the ocean and seaside communities.

In offshore marine reserves, ocean acidification is combated by increasing fish stocks. Teleost fish (also known as bony fish, which comprise about 96 percent of all fish) produce a chemical that acts as a buffer and counteracts some of the added carbon. This is not enough to stop ocean acidification – but the more fish in the ocean, the greater the buffer. Currently, there are fewer fish in the ocean worldwide due to overfishing and human activities that hurt fish habitat and breeding grounds. Past research shows that well-managed marine reserves increase fish populations and promote habitat recovery.

Helping Species Adapt

The new study also shows how marine reserves help species adapt to climate change. One of the biggest challenges that climate change poses is that habitats are changing faster than species can adapt. Marine reserves can help this challenge by increasing gene flow and providing refuge.

Typically, marine reserves give fish and other marine life populations the opportunity to grow, which creates more gene variation within the population. A larger gene pool increases the chance of adaptations that would benefit the population. Most supporters of protected areas advocate for a network of marine reserves that connect different populations and help facilitate gene flow.

As the climate changes many organisms find themselves needing to migrate to find better conditions. Marine reserves can act as a stepping stone for species on the move due to rising water temperatures. For organisms that cannot move, like coral, marine reserves allow for possible refuge.

For the Future

Creating marine reserves requires stakeholder participation and it can be difficult to facilitate different interest groups. However, the environmental and economic benefits are huge. Marine reserves are low technology and cost effective. Positive effects from creating more well-managed marine reserves would be seen from the local to global scale.

Marine reserves are by no means the sole solution to climate change. Ultimately, as a society, we must reduce climate-damaging greenhouse gas emissions. But the creation of more well-managed marine reserves can help with climate resiliency. Especially for the puffins, the lobster, and all of us in the Gulf of Maine who rely on a healthy ocean, the creation of more protected spaces is something that we must focus on – now.

New England has its own fully protected marine reserve, the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument – and it needs your help. Right now, it’s under attack by the Trump Administration, which is “reviewing” marine monuments and sanctuaries to gauge whether they will open them up to destructive oil and gas drilling. Take action today: Sign your name to let the administration know that our marine national monument protects our ocean treasures and must remain in place exactly as they are.