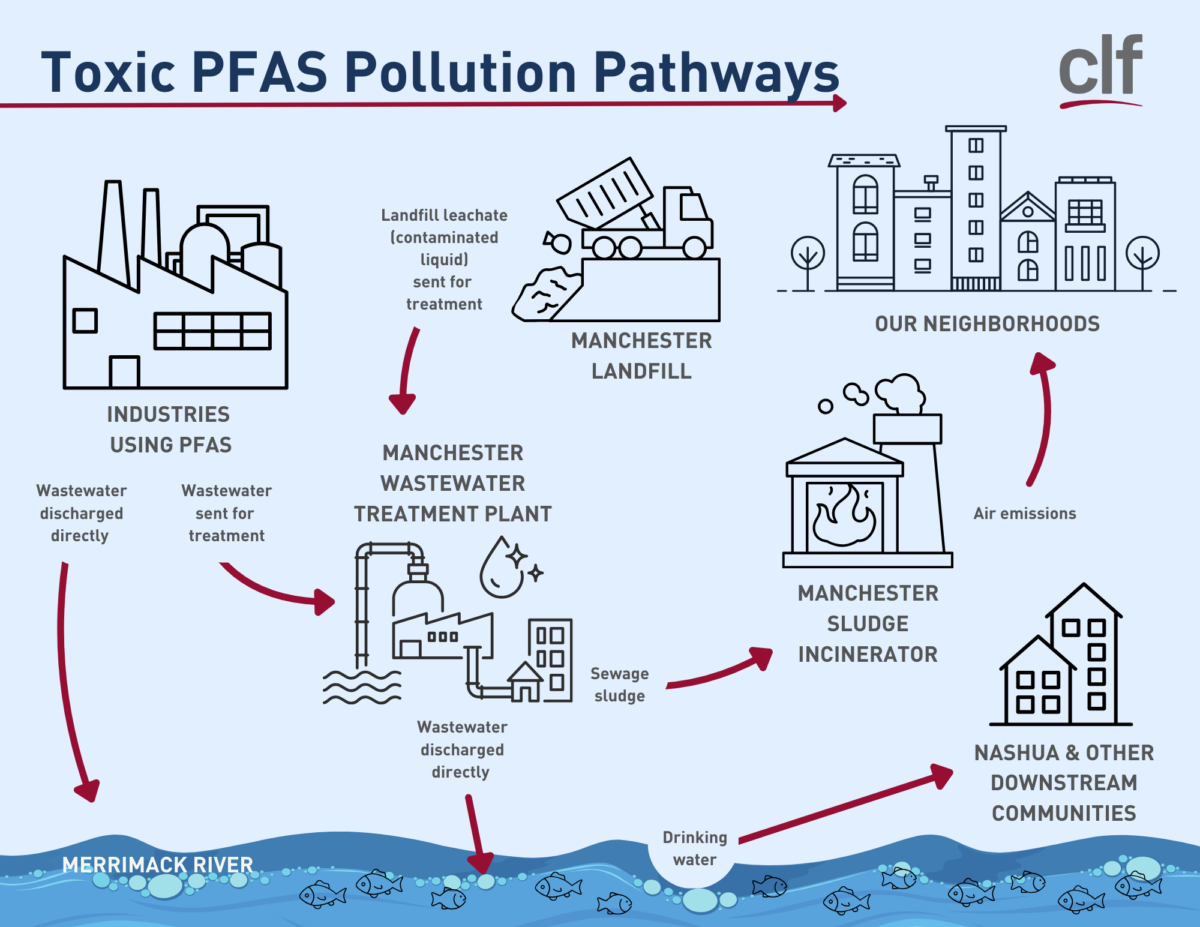

Treated wastewater from the Manchester treatment plant contains dangerous levels of toxic PFAS chemicals, which get released into our air and drinking water. Photo: Google Maps

Most people assume that once wastewater goes through the local treatment plant, what comes out the other side has been stripped of harmful chemicals or other pollutants. But when it comes to dangerous PFAS, or “forever chemicals,” the opposite is true. Wastewater treatment plants do not have a way to treat wastewater for these chemicals.

In Manchester, New Hampshire, the local plant releases its treated wastewater into the Merrimack River and burns its sludge in an on-site incinerator. These practices allow dangerous chemicals to be emitted into our water and air every day. This creates serious health risks for residents in Manchester and downstream communities, most concerningly for environmental justice communities already overburdened by pollution.

At CLF, we’re pushing the EPA and the City of Manchester to stop this pollution at the source. We want them to eliminate PFAS from industrial wastewater before it ever reaches the Manchester plant.

The PFAS Problem

You can find PFAS chemicals in industrial products and everyday household goods, such as cleaning products, nonstick cookware, and food packaging. Scientists have linked them with health harms like cancer, organ damage, and reproductive impacts. These dangerous chemicals can contaminate the water we drink, the fish we eat, and the air we breathe. And once in the environment, they’re nearly impossible to remove (which is why they are also called “forever chemicals.”)

Landfills and industrial facilities send PFAS-laden wastewater to the Manchester plant for treatment. But, as noted above, wastewater treatment plants like Manchester’s do not have the means to remove PFAS. So these chemicals remain in the treated wastewater and sludge – and that’s a problem for the health of our communities and our environment.

The best way to solve this PFAS problem is to stop “forever” chemicals from being used in the first place. That’s why CLF is advocating for the EPA and the City to require local industries that send wastewater to the Manchester plant to curb their use of these toxic chemicals. It’s also why we strongly support a New Hampshire state law, HB 1649, which will prohibit a broad range of products with intentionally added PFAS. This critical bill now awaits Governor Sununu’s signature.

Sources of “Forever Chemicals” in Manchester

Wastewater from landfills, called “leachate,” is one source of PFAS at the Manchester plant. Leachate is toxic liquid that forms when rainwater seeps through waste in a landfill. Two landfills – the closed Manchester Municipal Landfill and Casella’s active North Country Environmental Services landfill in Bethlehem – have been trucking contaminated leachate to the Manchester wastewater plant.

Manchester’s wastewater treatment plant has detected high levels of PFAS in the leachate it receives. For example, in February 2024, the plant accepted leachate from the Casella landfill with levels of PFOA, one type of toxic PFAS, roughly 155 times higher than New Hampshire’s drinking water standard. Those levels are also 467 times higher than the EPA’s drinking water standard. And, most alarmingly, they are 467,500 times higher than the EPA’s health-based interim drinking water health advisory level set in 2022.

The plant also accepts wastewater from various industrial facilities that operate in sectors known to use forever chemicals. These include a manufacturer of PFAS-based films, a metal finisher, a plastic producer, textile manufacturers, cleaning services, and hospitals.

Documented Pollution at the Manchester Wastewater Treatment Plant

The PFAS from landfills and other industrial sources ends up in the Manchester plant, which is not equipped to remove them from treated wastewater. Instead, the plant releases the treated wastewater – with the “forever chemicals” – into the Merrimack River. That endangers wildlife, contaminates fish, and threatens the drinking water source for more than 500,000 people in downstream communities. The plant’s incinerator burns the sewage sludge byproduct of the wastewater treatment process. In doing so, it emits forever chemicals into the air and increases health risks for nearby environmental justice communities.

Since 2019, the plant has consistently detected PFAS in the water it releases to the Merrimack River. A publicly available research study also documented the levels of PFAS in the sludge incinerator’s emissions. However, the City has not yet taken steps to reduce these “forever chemicals” at the plant or industrial sources.

The EPA and Manchester Must Lead in the Fight against PFAS

Now is the time for the EPA and the City of Manchester to stop PFAS from impacting the Merrimack River and Manchester’s air quality.

The plant requires a Clean Water Act permit from the EPA to discharge water into the Merrimack River. That permit is up for renewal right now. However, the agency’s permit draft only required Manchester to monitor PFAS in water and sludge. It fell far short of the EPA’s stated goals to address the PFAS crisis and advance environmental justice in four main respects:

- First, alarmingly, the draft permit failed to address environmental justice. That means the EPA didn’t follow its own Clean Water Act permitting policy. That policy recommends that agency staff analyze potential environmental justice concerns when drafting permits. It also highlights that, in many cases, agency staff have the power to eliminate or reduce disproportionate impacts on an environmental justice community. But in the case of the Manchester wastewater treatment plant, the EPA’s draft permit didn’t consider environmental justice at all.

- Second, the permit failed to require the plant to limit the PFAS it sends into the Merrimack River. Limiting PFAS in wastewater would help ensure that the river – which provides drinking water for half a million people and habitat for aquatic species – does not contain harmful levels of these chemicals.

- Third, the permit failed to require the plant to take actions to reduce the PFAS in industrial wastewater. Those actions could include the plant refusing to accept landfill leachate unless it’s first treated for PFAS. The plant could also require industrial dischargers to substitute PFAS products with non-PFAS products.

- Fourth, the permit didn’t include any requirements for the plant to monitor PFAS in air emissions from the sludge incinerator. That’s concerning because the EPA has committed to identifying sources of PFAS air pollution and pledged to better understand and address the human health and environmental impacts of PFAS in air emissions.

That’s why CLF recently responded to the EPA’s draft permit. We advocated for the agency to meaningfully consider environmental justice and include PFAS reduction requirements in the Manchester plant’s final permit. We also pushed the EPA to hold a public hearing on the permit to ensure that the agency meaningfully considers community concerns. If you’d like to stay informed about the status of the public hearing, sign up for email alerts from CLF.