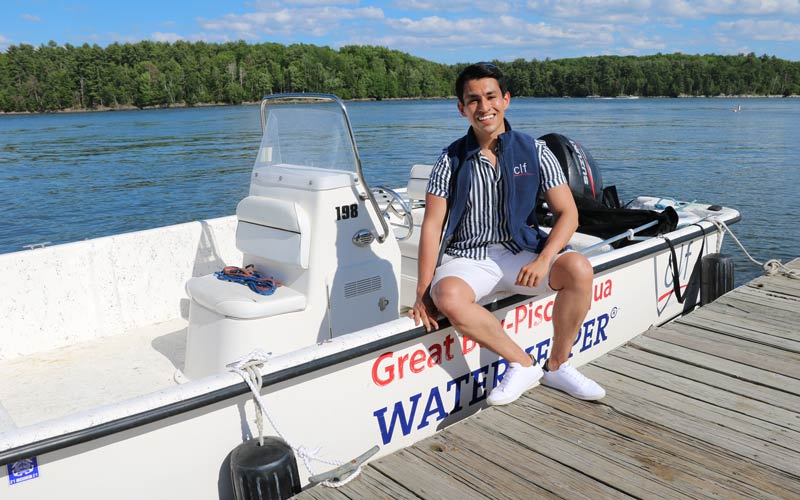

Through a eelgrass restoration pilot project, CLF and our partners hope to learn how to help bring life back to the Great Bay Estuary. Photo: Melissa Paly.

Last spring, I took up gardening as a hobby. I learned that, much more than enthusiasm, growing plants requires lots of dedication and hard work. But, if caring for plants at home sounds challenging, imagine how much harder it would be to grow plants under murky waters where we can’t control wind, weather, and tides.

CLF and our partners took on this challenge to find out if we can improve the health of the Great Bay Estuary in New Hampshire and southern Maine. Over the course of two weeks in May and early June, we harvested more than 7,500 shoots of healthy eelgrass and transplanted them across five locations in the bay. Due to stressors like nutrient pollution, suspended sediment, and disease, the Great Bay Estuary has lost much of its once-lush eelgrass beds. Through this pilot project, we hope to learn if it is possible to speed up the recovery of this plant – a keystone of a healthy underwater ecosystem.

I had the opportunity to take a field trip with CLF’s Great Bay–Piscataqua Waterkeeper, Melissa Paly, and lead scientists from the University of New Hampshire and Boston University as they worked on this restoration project. Here’s what I learned.

Water quality in Great Bay is improving, but we need to do more

For centuries, thousands of acres of seagrasses, like eelgrass, flourished across the Great Bay Estuary. But, over the last few decades, we witnessed a steady loss of this plant. With increasing development and population growth, nitrogen and other pollution from stormwater and sewage treatment plants have taken a toll on the bay. As a result, the estuary has lost nearly half its eelgrass meadows.

In recent years, CLF and our partners have pushed federal agencies and local authorities to act – leading to nearly $200 million in municipal investments to improve wastewater treatment. Thanks to these investments and other efforts, water quality has started to improve, and eelgrass has begun to make a comeback in some parts of the estuary.

That’s why, through this pilot project, CLF and our partners hope to test ways to speed up eelgrass’s recovery.

Eelgrass is key to water quality, healthy habitat, and diverse species

On my way to the estuary, the fresh morning breeze and sunny sky promised an exciting first visit to the Granite State, and it did not disappoint.

My train arrived in Durham, where I met up with Melissa. We headed out to UNH’s Jackson Estuarine Laboratory, a research facility located at Adams Point, where Great Bay and Little Bay meet. As we approached the water, the sounds and colors of the estuary overwhelmed my senses – the lively greenery moving with the wind, raucous bird songs, and gentle waves brushing against the shore.

When we arrived at Jackson Lab, I could see several people sitting outside around blue plastic kiddie pools. The pools kept alive dozens of healthy eelgrass shoots that the researchers had harvested at sunrise. Professor David Burdick, from the University of New Hampshire, took a shoot from the water and handed it to me. The eelgrass looked like long, thin ribbons, smooth to the touch, and whimsically colored in bright shades of emerald and lime green.

Each pool also contained a large metal frame, about five feet wide. As I watched, volunteers gently tied shoots to each frame with twisted strands of biodegradable paper. Once placed in the water, the frame will help the eelgrass stay down while it extends its roots into the sediment. I started to help, and, as I held the delicate eelgrass in my hands, Melissa shared her fascination for this aquatic plant.

In addition to filtering pollutants like nitrogen and phosphorus out of the water, she told me, eelgrass creates a home for shellfish and animals, produces oxygen, and keeps sediment in place. It also absorbs carbon dioxide from the environment and builds resilience against natural disasters. In an estuary, she said, healthy eelgrass meadows have the same crucial role that trees have in a forest.

It takes a village to turn the tide

After we finished setting up about a dozen frames, we loaded them onto the Waterkeeper’s boat and covered them with tarps to protect the plants from drying out. Then, the clock started ticking. Every minute the eelgrass spent outside of the water counted against its chances of surviving.

We moved quickly and set course to one of the planting locations that researchers had identified as a spot where eelgrass could potentially thrive.

Once there, two scuba divers jumped into the chilly, murky water. Carefully, two volunteers lifted the first hefty metal frame laden with eelgrass shoots and passed it to the divers. Clutching the frame between them, the divers disappeared below the turbid water.

On the boat, we watched their bubbles rise to the surface and waited with excitement. Underwater, strong tides and poor visibility made it hard for the divers to find the exact plots to place the frames. Once they did, though, they placed the metal frame into the bay’s sediment with the goal that the shoots will then take root and grow on their own.

Running against time, but with the same care, we repeated the process again and again – passing a frame loaded with eelgrass to the divers, then waiting as they carefully placed it under the water. Eventually, the team will return to recover the frames, with the goal that the eelgrass shoots will have taken root and started growing on their own.

In addition to using metal frames, our team tested another method – handplanting dozens of eelgrass shoots directly in the soft sediment. The research team hopes to find out which strategy can produce better results to help this plant recover.

Our team will keep an eye on this experiment

Over the summer, our team has kept an eye on the planting sites. And, this fall, we will gather the results and see how many plants set roots and survived.

If the experiment works and the eelgrass can thrive in these areas, the team hopes to scale up this project. But, even if the plants don’t survive, we hope to answer important questions about which methods, locations, and conditions might work better.

Ultimately, we want to learn more about how to accelerate the recovery of the Great Bay Estuary, while we continue other critical work to improve its water quality.

My hopes for the future of the Great Bay Estuary

I’m no expert in aquatic habitat restoration, but I know that with patience, care, and the right conditions, any plant can grow strong and healthy.

That’s why I’m hopeful that the eelgrass shoots we planted that day in May will set strong roots. But no matter what happens, we’ll be learning more about the Great Bay and how to help bring life back to those murky waters.

I can’t wait to go back to the estuary and see lush eelgrass beds. Maybe sometime in the not-too-distant future, I’ll even get to dive and explore clear waters teeming with fish and other critters.