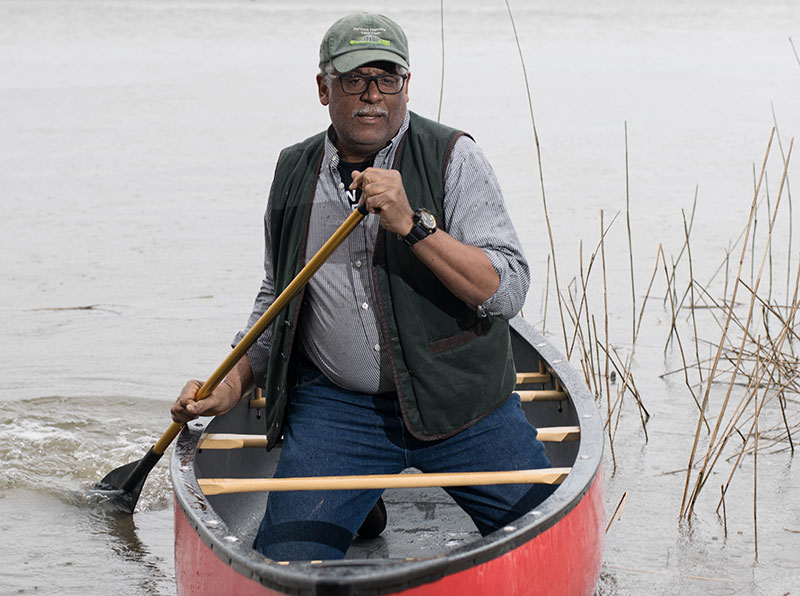

Fred Tutman founded the Patuxent Riverkeeper in 2004. He is committed to ensuring that communities own the work rather than approaching conservation from a top-down perspective.

In 2022, the country marked the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act. We’ve come a long way since 1972, when the country’s waterways were in crisis, flooded with toxic, cancer-causing contaminants so poisonous our rivers sometimes ignited into flame. As we celebrated the passage of a law dedicated to keeping industrial waste and sewage out of our lakes, rivers, and streams, we invited Fred Tutman to CLF to speak about his advocacy on behalf of the Patuxent River in Maryland. Tutman, one of the country’s few Waterkeepers of color, speaks candidly about his tireless efforts to challenge big interests while pushing the environmental movement forward. He’s surprised even himself in how long he’s stuck it out.

Tutman’s family has farmed and fished along the banks of the Patuxent River since the 1700s. His family still operates a farm in Prince George’s County. The grassroots organization he founded in 2004, Patuxent Riverkeeper, has worked on a range of issues and was pivotal in overhauling Maryland’s approach to regulating polluted stormwater runoff. His organization also helped obtain one of the largest settlements from a polluting wastewater utility in the state’s history. Here, his remarks have been adapted into a Q and A format and edited for length and clarity.

CLF: You’ve been advocating for clean water on the Patuxent for 20 years.

Tutman: I thought I was going to do this for five years. That was about as long as I thought I could afford to be a Riverkeeper. Ultimately the work captured me, and the challenge captured me. This is my favorite work of the many things I’ve tried and done in my adult career.

I’ve had probably three discernibly separate careers. Riverkeeping is the most challenging one, and it’s one where I have probably learned how to be myself more than any other. You’re kind of out there on a limb. You’re working with these communities where the aspirations are very high for the outcomes and where failure is brutal on morale. People’s lives are tied up in some of these cases and issues that we work on.

CLF: You’ve enjoyed a career in media, law, and legal education. What’s your approach to your environmental work?

Tutman: I think of our work at the Patuxent Riverkeepers as deeply community based. In fact, we insist on the funders not dictating the outcomes. So, many times, we don’t work with foundation funding. We’re funded instead by the communities that we serve, by earned income from kayak rentals at our visitors’ center, various contracts for services on the river, and other creative ways that keep us independent.

But the dynamic of communities owning their own work is hugely important because the community tends to pay it forward. It’s work that will stick around after the grants are gone, after the environmentalists have gone home. The work of the community remains within the community.

CLF: You’ve been very intentional in your community-first approach. How do you feel that differs from other organizations in the environmental movement?

Tutman: A lot of environmental organizations try to capture not so much hearts and minds but focus on capturing wallets. And we’re not on that page at all – as much as we also need to pay bills and sustain the organization.

But my point is that money-raising plays no role at all I in how we select the issues we work on. To the extent that we are not funded by or directed by “capitalism” means that we’re also free to fight it where we need to, which is often the case. We’re usually fighting very monied, and, frankly, very empowered interests who typically assume that their money, power, and influence can overwhelm a community-based agenda. Our community-based “kung-fu” has to be pretty strong. We cannot out-spend our opponents; we have to out-organize them!

The grassroots support for our work gives us an authentic moral claim to work on these issues. The community invited us in. The community is a partner in the work. The community has a lot of say over the outcome. Grassroots work is nothing like the opposite end of the spectrum, which would be work that is largely directed by some top-down interest trying to build a bandwagon that is controlled at the top of the pyramid.

We’ve lost patience with an establishment [large environmental groups] that straddles the line between trying to really solve these problems but also trying to appease an overall complex or system that is ultimately complicit in them. If you are inside these systems, it can be very hard to get perspective on precisely how to fight for change. That’s the power and advantage of being an outsider where insiders typically control the stakes.

CLF: Many communities, particularly lower-income communities and communities of color, are not well-represented in the environmental sphere. How do you make the movement more inclusive?

Tutman: I do believe that if you want to create meaningful diversity, the kind where people of color and all people feel comfortable in these movements, that’s not easily done. We’ve struggled with that. For my part as an African American, it was troublesome for me to be in situations where I essentially had people of color saying to me, “I don’t want to stay at your party because the white folks want to talk to each other but not to us. The vocabulary is kind of confined to the things that they like to talk about, but not what we like to talk about.”

People of color will invest ourselves in these clubs and movements to the extent we feel valued and that we can make a contribution that is bigger than just being “the diversity.” That is just not enough to connect people of color to movements that sometimes regard us as an afterthought but not as vital and fundamental to these organizations.

So, I do see that a lot of these environmental issues we work on are multifaceted. Depending on where you sit on the continuum, they might appear entirely different to one person than to another. On one hand, whites who insist these (large organizations) are perfectly great organizations – even without people of color in them; and on the other hand, people of color who want to be ourselves in places and spaces where we truly matter and have some ownership and potential.

CLF: As a Riverkeeper, you say that you’ve noticed egregious examples of how the environmental movement might fight to save a particular animal or plant species without considering the grave injustices done to people. Are environmental groups sometimes out of sync with the communities they purport to represent?

Tutman: We work very hard, I think, to level the playing field away from movements that culturally are “insider movements.” We think of them as social pyramid schemes where the prime benefits go to the prime members – essentially groups that don’t actually discriminate against anybody, but decidedly have a preference and a tradition for serving whites. The culture of these groups suggests that these are movements for people in the know, but not so much for every man or every person.

But I think that is deeply challenging if you want the moral authority to work on these issues and to speak for as many people as possible. In the Waterkeeper movement, we struggle with this as well. We have what we call an exclusive jurisdiction for the waterways that we work on, but the exclusive jurisdiction shouldn’t give you the right to run an exclusive club!

CLF: You talk about the difficulty of breaking through the “fourth” wall, trying to talk to people and communities you’ve never talked to before to better understand their problems. Are you succeeding?

Tutman: Yes, there are moments when you know you are really breaking through – truly communicating and operating in a sphere far and beyond what you dreamed was possible, while building both powerful and empowering, equitable movements. It is revolutionary and deeply transformative work – if done properly. In our office, we actually ask ourselves almost every day, “Is today the day we’re making a living, or we’re making a difference?” We’re not sure we can always do those two things at the exact same time. There are concessions we have to make sometimes just to keep the lights on. But the focus is clearly on trying to change these systems and make a better society environmentally and on all levels.

Learn more about Fred Tutman’s work the Patuxent Riverkeeper, and find more about his journey to become a riverkeeper in this story on Waterkeeper.org