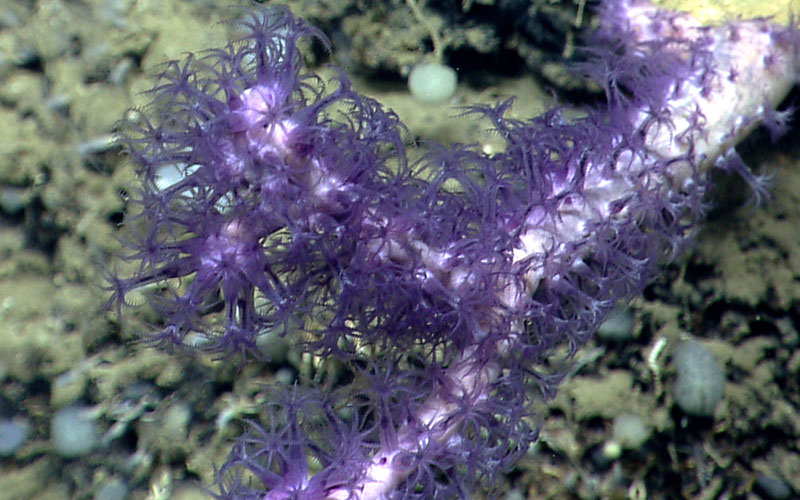

Photo courtesy NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program

When thinking about New England’s ocean, marine life like lobster, cod, and humpback whales might come to mind. Corals, on the other hand, might not make the list – though they should: New England’s ocean is home to many rich, vibrant, colorful deep-sea coral communities, some of which likely include organisms more than a thousand years old.

In New England, deep-sea corals can be found close to shore in the Gulf of Maine, but they more commonly inhabit the deep canyons on the southern flank of Georges Bank off Cape Cod. They are also found along the continental slope and the seamounts rising dramatically from the seafloor.

Given that these creatures are found in the “deep sea,” the corals might seem naturally protected by their geography – but these fragile organisms are actually exceedingly vulnerable to human impacts, predominantly from commercial fishing gear. One pass of an otter trawl or the random landing of an offshore crab or lobster trap could destroy hundreds or even thousands of years of corals’ growth. If that happens, not only are the corals irreparably damaged, but important habitat for fish and invertebrate species are gone, too.

Newly-Passed Amendment Offers Progress in Protecting New England’s Fragile Corals

Last week, the New England Fishery Management Council approved the Omnibus Deep-Sea Coral Amendment, using its discretionary authority under the Magnuson-Stevens Act, our nation’s federal fisheries law.

Overall, this amendment is a win for New England’s ocean, protecting more than 25,000 square miles of fragile seafloor habitat. As a result of this and other measures, nearly 100,000 square miles of deep-sea coral habitat is now protected along the U.S. east coast. We appreciate that the Council has protected more coral habitat than they ever have before – but we can’t help but examine the process behind this management decision.

A Missed Opportunity

The Council vote focused on creating a broad coral protection zone in the canyon area south of Georges Bank. Two options were on the table: the first was a measure restricting fishing vessels using bottom-tending gear (gear that rests on the ocean floor, including fishing trawls and lobster pots) from operating deeper than 600 meters in the specified zone.

The second was a “nested” approach, specifying the same 600-meter depth limit for fixed bottom-tending gear and a 300–550-meter depth limit for all mobile bottom-tending gear (gear that is towed by a fishing boat, such as an otter trawl).

This second approach incorporated the most recently available data about where corals are located and where fishing currently takes place. Using that data, it drew a boundary that would protect the maximum amount of corals while minimizing any impact on the fishing industry. If there was evidence of coral habitat but not fishing, then limits on gear would start at 300 meters. If the data showed both coral habitat and fishing (or no evidence of either), then gear would be prohibited below 500 meters’ depth. And, in an area with fishing but no coral habitat, the limits on gear wouldn’t start until 550 meters deep.

By contrast, the first option only protected corals that were deeper than any foreseeable future fishing effort.

Seeming to largely ignore the extensive analysis, time, and money invested by their own experts as well as outside groups in developing the second option, the Council voted for the first – the 600-meter provision that was largely based on last-minute conjecture from some in the industry.

The selected 600-meter depth limit leaves significant corals and their habitat areas, which could have feasibly been protected, vulnerable to irreparable damage from fishing gears (and without rational justification). Further, it allows for the expansion of fishing efforts into new coral habitat areas that aren’t currently fished – contradicting any claims that they were following the lead of other regional councils and “freezing the footprint” of current fishing on the ocean floor.

Some say that the 600-meter option was the “right” one because it had the commercial fishing industry’s support. But the Council shouldn’t exist to only make decisions based on industry support. It should be there to make the hard decisions that safeguard the long-term health of New England’s ocean resources, on which our fishing industry depends – and take the heat when necessary.

We appreciate that the newly appointed NOAA Fisheries Regional Administrator Michael Pentony strongly expressed his support for coral protections based on the best available data – and therefore the second approach – and are disappointed that the Council chose not to go the distance.

Keep on Fighting

The Council had an opportunity to provide greater ecological benefits while still minimizing economic impact – but they resoundingly chose not to take it.

CLF has a long history with the New England Fishery Management Council and with ocean habitat protection in New England. Since 1989, we’ve advocated for sustainable, science-based fisheries management. The health of our ocean requires that we continue to fight for the protection of our most valuable ocean areas and resources for future generations. Deep-sea corals may be out of sight, but they are not out of mind here at CLF.