Years ago, Zeyneb Magavi was preoccupied with renovating her home to be safe and sustainable.

Working in global health and having two young toddlers at the time, one of her driving concerns was finding a way to keep her family warm without burning fuels. So, she did her research.

“I put in all this effort and time,” she recalls.

While researching, Magavi stumbled on one form of home heating that seemed to check all the boxes. It was efficient, non-polluting, and, once installed, inexpensive to run. There were none of the health risks associated with natural gas. Not many people were talking about it at the time: geothermal heating, that is, using the warmth stored deep within the earth to heat buildings.

That was nearly two decades ago. Since then, Magavi’s wisp of an idea has flowered into a full-blown global mission. Today, she is the executive director of HEET, a Boston-based nonprofit (and a CLF partner) dedicated to leading a thermal energy geothermal revolution. She sees geothermal networks linking hundreds of homes and businesses through pipes snaking deep underground as part of “an ethical and efficient thermal energy transition.” And that transition entails moving people off combustible fuels to heating and cooling their homes using a clean and abundant heat source stored just beneath their feet. Tapping that natural heat could happen, she argues, if gas utilities become thermal utilities. And she’s working on doing just that.

If we hope to live on a planet free of the harmful impacts of climate change, she says, “[geothermal heat is] a major piece of the puzzle that we need to get there.”

Moving from Gas to “Geo”

When Magavi first saw the possibilities of geothermal years ago, she talked with companies in the field and even the City of Cambridge about bringing geothermal heat to her home. Ultimately, she gave up on the idea because of the expense of bringing geothermal to just one house. However, years later, while working on her master’s thesis in sustainability, she spent a summer out with gas trucks and their workers, measuring some of the thousands of gas leaks from pipes coiling around the city. The experience, she says, “taught me a huge amount about the gas utility system and its risks. Including the risks those workers I spent time with take every day, but also the economic risk of rising prices to the consumer.”

What she wanted to know was whether there was any alternative. Suddenly, her experience with gas workers and her previous interest in geothermal clicked like two Lego blocks.

“What if you turned a gas utility into a geothermal utility?” she asked herself.

Before, when she had considered bringing geothermal heat to her home, it was beyond her budget, primarily because of the high cost of hauling drilling rigs to bore into the depths of the earth to service one house. But gas utilities routinely burrow to install pipes, and they do it for many homes at a time. They’re also comfortable with substantial upfront costs. Plus, they know the gas game is up. State laws requiring deep cuts in carbon pollution mean that, sooner or later, gas utilities will be out of business. But one elegant solution solves all these problems at once: converting gas utilities to geothermal ones.

“I get the lowest-cost heating and cooling known to man, and the gas companies get to survive!” says Magavi.

How Geothermal Energy Works

Magavi’s fascination with geothermal energy is born of a background in physics and a natural tendency to problem-solve. She knew that the shallow bedrock in Massachusetts holds steady at a stable 55 degrees F, both winter and summer. When the outside air temperatures dip, that represents a lot of warmth. Geothermal taps this heat using a piping system called a “loop” to circulate water between the earth, a ground source heat pump, and a home.

Geothermal networks go one step further by connecting not just one home with the year-round warmth beneath the Earth’s surface but entire communities. By laying pipes filled with water under streets, as we have for gas, we can suddenly have a viable heating source for whole neighborhoods and cities. The water in these pipes absorbs the ground temperature of the earth and delivers it to buildings. The pipes also connect buildings with different heating needs, so energy never gets wasted. Instead, it is exchanged between buildings or stored in the ground until needed. In the winter, the heat pumps move heat from the ground into the home, and the process is reversed in the summer to keep buildings cool.

The idea of burning anything to stay warm seems sheer lunacy, says Magavi, when you consider all the heat in bedrock, the rivers, and the sea.

“In an act of both energy efficiency and restoration, it becomes very obvious why we need to build thermal energy networks and transform our gas utilities into thermal utilities,” she says.

Putting a Good Idea to the Test

Magavi had the idea, but would gas utilities be interested? Turns out, they were. After she approached the utilities with her idea, they saw enough promise to sign on.

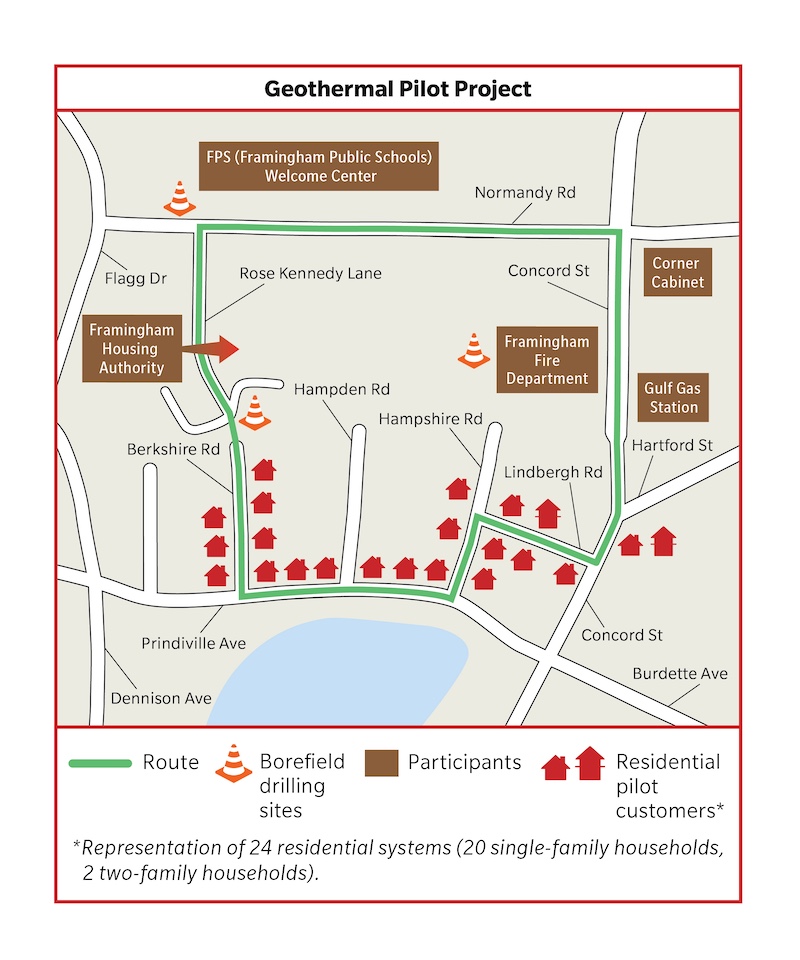

In the fall of 2022, Eversource broke ground in Framingham on the country’s first gas utility-installed networked geothermal system. HEET gathered a team of researchers from UC Berkeley, MIT, and Boston University to collect data on the pilot project of 130 buildings now connected by “geo” pipe on a mile-long main loop. Seven commercial buildings, a fire station, a school, dozens of single-family homes, and apartments owned by the Framingham Housing Authority are now heated and cooled using the heat beneath the city. Residents are expecting to benefit from substantially lower utility bills despite now using air-conditioning they didn’t have before.

A Natural Transition for Gas Workers

The pipe installation was a natural transition for gas workers, who moved easily from installing gas pipe in our streets to installing geo pipe. (The gas pipe was not reused for geo. Although the pipe is the same kind of pipe, the size needed is often not the same.)

“Some of the [gas workers] arrived in Framingham having put in gas pipe the day before,” marvels Magavi. “They put the pipe in the street pretty much on time, on budget and it seemed that the pipe going in the street was the smoothest part of the project. Then they were done, left, and went back to putting in gas pipe. It was probably the smoothest workforce transition we can ever imagine. And the gas workforce is game and ready to put in more.”

According to Magavi, 29 gas utilities have joined the “Utility Networked Geothermal Collaborative,” covering 50% of all U.S. gas customers and over 60% of Canadian ones.

Priced for the Long Term

Although $10 million was budgeted for the Framingham project, ultimately, the cost reported to the state DPU was $17 million. Magavi attributes the cost overruns to pandemic supply chain issues, inflation, a steep learning curve, and the demand for geothermal drilling becoming so high that costs have shot up. But, she says, costs must be compared to the alternative. According to HEET, utilities in Massachusetts will have spent $42 billion between 2015 and 2039 replacing aging gas pipes. Those costs will get passed onto gas customers.

Instead, she argues that investing money in geothermal systems that will last beyond the goal of zero carbon emissions by 2050 is better. Because the pilot project showed such promise, other geothermal projects, including National Grid projects in Boston, are underway.

Magavi says the real problem is retrofitting New England’s older, often neglected building stock to accept the geothermal energy once it arrives at the door. She saw this challenge in Framingham when Eversource converted buildings built well over a century ago, originally as military housing, to geothermal.

“Buildings in Framingham have the same issues that you and your home might be facing, such as old wiring, asbestos, and mold for example,” she says. “It was representative of the challenge we face in Massachusetts and something we should all be paying attention to.”

Even with these problems, to her mind, turning to gas utilities to build out a geothermal infrastructure is a no-brainer.

“You already have an entire workforce; you have an entire interface with the municipalities; you have a full customer interface and billing interface; you have an entire sales team; you have a massive financing mechanism; you have load management,” she says.

A Cleaner, Brighter Future

To be sure, other issues need to be resolved. Geothermal energy can’t do it all everywhere. But it could play a big part in the move toward clean energy in Massachusetts and worldwide, Magavi maintains. She recently returned from meeting with Middle Eastern and Central Asian countries, including Turkey, Pakistan, Jordan, Kazakstan, and Ozbekistan, all of which are now considering building geothermal energy networks.

“The IFC, part of the World Bank Group, has recently identified geothermal networks as an effective technology that can meet sustainable development goals, including decarbonization, in a cost-effective way.”

While working to scale geothermal networks, Magavi, through her organization HEET and with funding from CLF, is focusing on weatherizing homes and reducing energy bills in low-income communities. HEET has also been focusing on ensuring low-income communities are included in the energy transition, as well as working to reduce methane leaks. These leaks remain a massive source of methane emissions and are prevalent in low-income communities and neighborhoods of color. These are also the neighborhoods that experience the most health issues from pollution and climate change due to discrimination and historic redlining.

Geothermal energy is still far from becoming a primary energy choice for all of us, but Magavi is optimistic.

“I think it’s going to happen,” she says.