Boston’s biggest and most diverse neighborhood, Dorchester, used to be its own city, and it can still feel that way. You can get a delicious Vietnamese banh mi sandwich on one block and Cape Verdean cachupa stew right down the street. The annual Dorchester Day Parade showcases bagpipers and Caribbean dancers alike.

The neighborhood has a rich history of community leadership, but government redlining and disinvestment in the 1960s and 1970s harmed the neighborhood. Boston banks racially segregated the city by restricting where Black homebuyers could get a mortgage, and Dorchester fell within a literally redlined boundary.

Now, as more people want to live closer to the city center, newly built Dorchester apartments charge an increasingly high monthly rent. Those rising rents are pushing out long-time residents, most of whom are people of color, and threatening to change the character of the historic neighborhood.

But on Talbot Avenue, a new apartment building is bucking that trend. Developed in partnership with the people already living in the area, 191 Talbot Avenue adds 14 new homes to Dorchester’s housing stock. Rents here lock at rates below market price, allowing neighbors to stay in their community.

For developer Travis Lee, collaboration with community groups was key from the project’s beginning. Even before purchasing the land, he talked with neighborhood residents about what they wanted to see built – and where they wanted it.

Lee has lived in the neighborhood for 15 years. He moved to Boston in 2003 to work at a homeless shelter, an experience that shaped his understanding of how health, housing, and economic development intertwine. After working with the community-driven Madison Park Development Corporation, he started his own company to build moderately priced mixed-use properties in his neighborhood.

With the Talbot Ave project, Lee didn’t just want to build a new apartment complex and then cash in on the gentrification trend. “I’m building housing for people I either know or will get to know. I want people to live in a place where I’d want to live,” he said. To solicit input, Lee attended community group meetings and hosted conversations himself, including one with the senior home next door to the property.

“It’s a huge deal for the neighborhood,” said Paul Malkemes, who leads the civic group Talbot-Norfolk Triangle Neighbors United, which provided input on the project. “Every other private development project up until that point was around the scenario of someone who had already bought land and wanted to figure out what to put there. Travis began the conversation with the neighborhood first. It stopped us from feeling like we were being forced to figure something out that we didn’t really want.”

One idea that the developer and community members all agreed on was a desire to build energy-efficient homes. Their collaboration led to the apartments meeting “Passive House” standards, meaning that, through good building techniques and insulation, the homes require very little energy to heat and cool. That, in turn, lowers monthly energy bills for residents.

And the lot where 191 Talbot is going up? It was once a gas station. Its transformation into energy-efficient affordable homes is a symbolic trajectory.

That trajectory also encapsulates the mission of the Healthy Neighborhoods Equity Fund (HNEF), which provided capital to Lee for the complex at 191 Talbot. Created through a partnership between Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) and the Massachusetts Housing Investment Corporation (MHIC), the Fund invests in developments that will have a “quadruple bottom line” – not just financial returns but also positive impacts on the community, environment, and health.

By providing funding for the development of affordable, green housing like 191 Talbot Ave, the Healthy Neighborhoods Equity Fund takes on the big, intersectional issues of climate change, public health, and housing stability.

It’s a systemic solution to systemic problems. The Fund’s approach upends the conventional thinking about real estate and development that’s all about financial profit.

“The intent of the Fund is to invest in transformative change that neighborhood residents have envisioned for themselves,” said Maggie Super Church, who leads the Fund’s work at CLF. “We want to help create the kinds of places residents want to be in and stay in.”

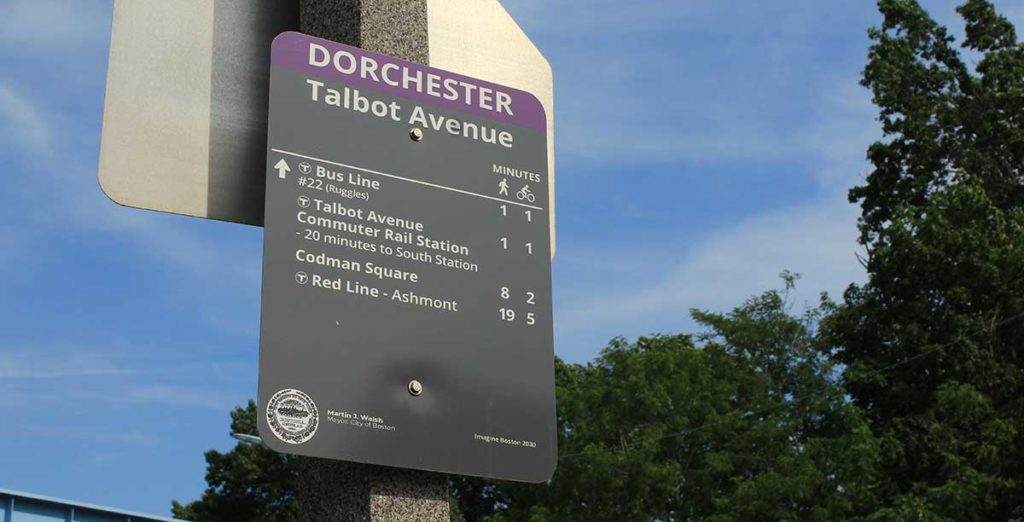

To receive money, developments must receive a minimum rating on the Fund’s HealthScore, which ranks elements such as affordability, access to green space, neighborhood walkability, and low-carbon building. For developers like Lee, the HealthScore checklist ”was a match made in heaven. The Fund’s criteria were already my criteria. I believe in really high-quality indoor air, in walkability, easy transit downtown, access to green space,” he said.

The apartments at 191 Talbot Ave represent the last of nine projects in the Greater Boston area in which the Fund invested its initial round of financing. Now that those are wrapping up, CLF and MHIC are turning their focus to a second round of funding. For this next phase of the work, the HNEF team has updated the criteria developments must meet to receive an investment, including an increased emphasis on residential energy efficiency and community involvement.

Energy efficiency may not be the first thing that comes to mind when you think about climate, housing costs, and health. But it’s actually one of the many multifaceted ways a development can help address all three challenges at once.

“There are three parts to it,” Lee summarizes. “One of them is the environmental friendliness. The other one is the low cost. And the third part is the health of the human being that’s living there.”

Americans spend an estimated 90% of their time indoors (according to a pre-pandemic study), and inefficient HVAC systems can lead to uncomfortable fluctuating temperatures, mold, and asthma.

Inefficient home energy systems also factor into housing affordability. Nearly a third of U.S. households struggle to pay their energy bills. One in five has used money that would have gone to food, medicine, and other necessities to pay their energy bill at least once, if not more often. These cost burdens disproportionately affect communities of color, who tend to live in older, draftier, and less efficient homes.

An energy-efficient home can lower bills and make the indoors a more comfortable and healthier place to be. On top of those individual-level benefits, using less energy is also necessary to hit targets for cutting climate-damaging emissions community- and state-wide.

But without the structure of HNEF’s investment requirements, developers might not choose to build energy-efficient homes, even though they’re the better choice for residents and the planet. Or they may build efficient homes, but at a rent that’s unaffordable for many residents.

“I’m part of a design and construction team that only builds passive homes,” Lee said, “and there’s an up-front cost. The hope is that over time, the tenants pay a much lower utility bill, and it makes a difference in their long-term well-being.”

As CLF updated its HealthScore to place greater emphasis on ownership of change, it drew on research from the organization’s Healthy Neighborhoods Study. Its findings show that community members who feel ownership of the changes happening in their neighborhood have better mental health. The study also pinpoints the difference between gentrification and improvements to the area that residents want for themselves.

How do you reach actual “ownership” over neighborhood change? It begins with the sharing or transfer of decision-making power from traditional authorities like a developer to the residents impacted by proposed neighborhood changes, as Lee did when creating 191 Talbot.

“‘There’s never been a moment with Travis where he was trying to force something on the neighborhood,” Malkemes said. “It’s a very different and freeing position.”

That process started before the land was even purchased, a reversal of how development often happens. Developers in the Boston area have their eyes on Dorchester as a neighborhood that still has vacant lots close to transit, but most buy the land then work out how to make money on the purchase.

“Many developers purchase a property and then approach the community for support,” Lee said. “Unfortunately, at that point, the developer and community are cornered, as the developer likely needs a certain density and unit count to make the numbers work — there’s no longer room for discussion or flexibility.”

Lee even created a community-driven process to pick the retailer for the ground floor of the new development, adding another layer of self-determination for the people in the neighborhood. They chose to bring Fresh Food Generation into the space, citing the restaurant and catering business’s dedication to hiring from the Dorchester community and paying living wages.

“We’re so thankful to be able to move into this space where the community has expressed wanting us to be there,” says Fresh Food Generation founding partner Cassandria Campbell.

Opening up at 191 Talbot is about more than finding a permanent home for the growing food business, which focuses on making fresh healthy food more accessible. “I’ve lived in this community, I went to preschool at the Lee School, which is adjacent to 191 Talbot,” says Campbell. “It’s home in a way I can’t really explain. I think about all my childhood memories, and I never would have imagined opening a restaurant there.”

Lee was equally committed to ensuring that the people tasked with actually building the new development looked like the people who live in the neighborhood. To date, the project has directed 78% – $2.7 million – of construction contracts to Black- and Brown-owned businesses. People of color performed nearly 90% of the work hours.

Bending the market toward a more just approach lies at the heart of CLF’s mission to support healthier communities for all. The HealthScore is a first-of-its-kind assessment tool linking new development to health – and acknowledging that ownership of change is part of a healthy neighborhood. For Super Church, building a financing system that encourages developments like Lee’s was a challenge worth taking on.

“We worked so hard for so long to convince people to do things they thought were crazy,” Super Church said. “Creating this out of thin air was a lot of work, but part of our job here should be to show people what the future can look like if we get it right.”

For the residents and businesses who can now call 191 Talbot Ave home, the future is today.