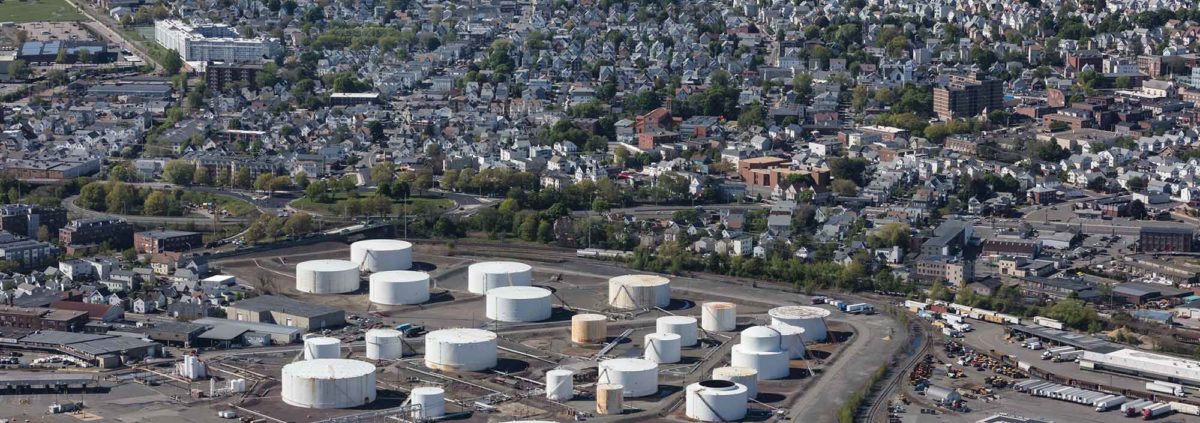

Darrèll Brown drives down Providence’s Allens Avenue several times a week. On both sides of the busy road, Shell Oil’s massive oil storage terminal looms. Each of its squat white tanks reaches 50 feet high and stretches even wider. The sight of them serves as a stark reminder of the risk of pollution from the tanks every time it rains – and the silent threat of the catastrophic damage they could unleash when hit by a powerful storm.

“It’s an intimidating stretch of road,” Brown says. “It feels dangerous.”

As vice president for CLF’s Rhode Island advocacy center, Brown actively works to hold Shell responsible for the harm its facility could cause and to prevent a massive spill in the future. CLF has sued Shell Oil for failing to accurately report what pollutants its oil storage terminal releases into the Providence River and for neglecting to prepare its facility for the impacts the company knows the climate crisis will bring.

Despite the oil giant’s attempts to get the lawsuit dismissed, the case is moving forward. It marks the first time a private fossil fuel entity will need to answer fully for its knowledge of climate change

and its risks.

“It’s Not a Coincidence”

The oil terminal in Providence sits at sea level on filled land in the Washington Park neighborhood, a diverse working-class community. While the entire Narragansett Bay and surrounding area would be impacted by an oil spill, the people living closest to the terminal endure its harms already: worse air quality, respiratory illness, and noise pollution from huge trucks going in and out of the facility.

“There’s a sense of powerlessness in the neighborhood,” says Brown. “There’s the community, and then there’s this big oil company with lots of money. Black and Brown communities are disproportionately affected by this kind of pollution. It’s not a coincidence.”

It’s not just Washington Park residents who live with the daily risks of pollution and the looming threat of an oil spill. Across New England, oil and gas company terminals and storage tanks are often located in environmental justice neighborhoods: communities of color, low-income communities, working-class communities. And Big Oil’s operation of those terminals leaves these communities vulnerable to severe weather and risks of pollution.

“It’s simply outrageous how ExxonMobil, Shell, and other companies have ignored the climate science and risks,” says CLF President Brad Campbell. “They’ve acknowledged it internally. But in the case of communities that are in harm’s way, the communities that have hosted these facilities for generations, they’ve essentially ignored those risks.”

Just north of Boston, ExxonMobil’s large petroleum storage facility poisons the Mystic River and its Everett community daily [see sidebar on page 7]. South of Boston, the Sprague Energy terminal in Quincy – one of the most at-risk cities from rising seas, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists – could spill millions of gallons of oil into nearby waterways and neighborhoods. In New Haven, three oil companies’ facilities – Gulf, Magellan, and Shell – sit precariously on or near the banks of the city’s harbor.

CLF is taking the oil giants to court in partnership with residents from the Everett, Providence, New Haven, and Quincy communities they’re harming. These lawsuits are the first of their kind, suing Big Oil companies for climate risks and pollution under the Clean Water Act and hazardous waste law. CLF filed the first of its lawsuits against Exxon in 2017, with the others following in the years since. Nationally, many states and local governments have filed lawsuits seeking to hold companies accountable for climate change risks and deceit. CLF’s are the first cases focused on climate resilience to head to trial.

It’s Not If, But When, the Next Big Storm Comes

The looming danger these facilities pose is not a matter of if but when a big storm comes. Climate change – caused by the very petrochemical products the oil companies profit from – is intensifying hurricanes and pushing them into increasingly warm waters farther north in the Atlantic. We’re seeing everyday rainstorms grow more intense and frequent. Sea level rise is happening faster in New England than most other places in the U.S. According to NOAA, the sea level off the Massachusetts coast is eight inches higher than it was in 1950. And it’s now rising even faster – about one inch every eight years.

Fossil fuel facilities like those in Providence, Everett, Quincy, and New Haven are not prepared for increasingly intense rainfalls and flooding, let alone a hurricane or tropical storm. The communities living near them have no assurance that they will be protected from the pollution that would swamp their streets if one of these facilities flooded.

We don’t have to imagine the damage a hurricane can cause, however. When Hurricane Harvey hit Houston in 2017, petrochemical facilities released thousands of barrels of oil into the floodwaters that destroyed 100,000 homes. They spewed an estimated one million pounds of hazardous pollutants into the air, causing short-term nausea and long-term elevated risk of cancer in the residents forced to breathe them in. Harvey was a Category 4 storm, but it would only take a Category 1 storm surge to flood the Shell terminal in Providence or Exxon’s Everett facility. New Haven, meanwhile, suffered significant damage from Hurricane Sandy in 2012. But it would have been much worse had the storm surge coincided with high tide. Harborside neighborhoods could see even more destruction a second time.

It’s not just a catastrophic flood from a hurricane or tropical storm that concerns community members. These facilities are also violating the Clean Water Act by risking regular toxic discharges, which get swept up in rain and floods into nearby waterways and surrounding communities. Those waterways are already unsafe for fishing, swimming, and other recreation. With the 70% increase in intense rainfall already seen in New England, the risk of regular, ongoing harms from these facilities is also increasing.

populated neighborhoods that would be devastated by a toxic flood. [Photo: Alex Maclean]

Deceit and Denial

In arguing their case in court, CLF’s legal advocates will not only use the best science and engineering to show current climate risk. The legal team will also present each company’s own statements – dating back decades – documenting their deep knowledge and consideration of climate change and severe weather risks in their operations.

Exxon scientists predicted as early as the 1970s that burning fossil fuels would cause the climate crisis we’re currently living through. Several other Big Oil giants also conducted research into how fossil fuels harm human health and damage our climate. That means they also knew the danger they put communities in. Yet they have continued to prioritize their own profit over the health and safety of people and the planet.

Instead of spending money to protect coastal communities, they’ve spent 50 years and millions of dollars sowing climate doubt and deceit. Even now, as the companies try to talk up their green energy efforts – while still drilling for oil and gas – an Exxon lobbyist was caught on tape just last year discussing explicit strategies to stop climate action in Congress.

“The connection between that deceitful conduct and the risk to human health and the environment couldn’t be clearer,” Campbell says. “Our lawsuits are an opportunity to remedy that wrong. And they are an important opportunity to reduce risk for our communities in harm’s way.”

If CLF’s lawsuits are successful, the oil giants will be forced to update their facilities for the climate risks they’ve known are coming.

“Over the years, Shell and other oil companies have been sowing doubt and deceit about what they know and when they knew it while failing to properly prepare their facilities for climate change,” Brown says. “What that tells me is that they have really made profit more important than the lives of people and the health of the community. There’s no other way to say it.”

Photo at top: Shell Oil’s Providence terminal spans heavily industrialized Allens Avenue – with the Providence River bordering the facility on one side and the Washington Park neighborhood on the other. [Photo: Ecophotography]