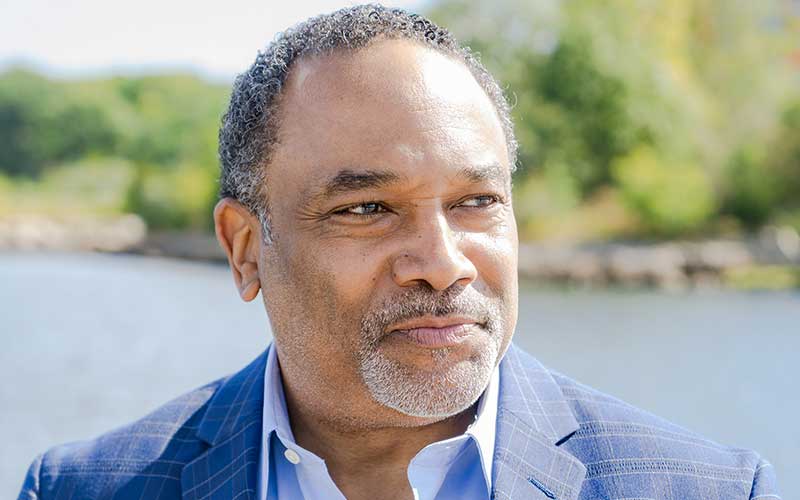

Darrèll Brown has experienced systemic racism throughout his life – personally and professionally. He joined CLF to fight against policies that drive systemic and institutional racism.

In her book, The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together, Heather McGhee asks a simple question: Why can’t we have nice things? After reading the book, I kept returning to the question.

As a Black man who grew up and came of age in this country, I know that racism is real. I know it can be individual. I know it can be institutional and structural, supported by law, institutions, and culture.

I have experienced the hurtful and harmful sting of racism in most of its modern-day forms. I know that my father, my mother, my grandparents, my aunts, my uncles, cousins, and friends share those experiences. I know that racism is still all around the sum of us. But why?

People of color have been deliberately left out of the conversation

I have spent my entire professional life in the service of others. I have been a dedicated public servant. I have worked to satisfy not just my own needs and ambitions but to help others to do the same, regardless of race, color – or whatever their background.

Years ago, I fell into the field of economic development. At that time, some 25 years ago, people of color were few and far between in the field. I wondered why. Over time, I became aware that, contrary to the assumptions of many in my profession, the dearth of people of color did not result from a lack of interest or an unwillingness to participate. My primarily white colleagues did not want people of color involved. They did not want people of color engaged. They did not want people of color to learn how they could improve their lives, communities, and families.

It was just that simple, and I felt it. But, as I later learned, there was more.

Racist policies have been pervasive in transportation, housing, banking, and more

Indeed, people of color tried for decades to engage and build their communities through economic development practices, only to have those efforts blocked, time and again. The most prominent example is the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma, race massacre, in which a white mob literally burned down a vibrant and economically accomplished Black town. It wasn’t always violence that perpetuated injustice, however. When serving as director of economic development in Charles County, Maryland, I watched in real-time as gentrification forced Black people out of Anacostia in southeast Washington, D.C., entirely.

These are hardly isolated occurrences. Florida, California, Georgia, Maryland, Louisiana, and other parts of Washington, D.C., are just some of the places that experienced this systematic racism. Despite the best efforts of Black communities, discriminatory policies and practices endemic to transportation, housing, and banking – to name just a few – blocked their progress.

I witnessed firsthand how these sectors targeted communities of color for disinvestment through redlining, illegal dumping, and draconian drug policy. Zoning regulations produced a proliferation of liquor stores and strip clubs in those communities. They were also condemned to inadequate-to-no healthcare services, limited access to public transit, and a lack of clean public spaces. All of this, mind you, was coupled with over-policing and police brutality.

Environmental racism has been just as harmful

I like to think that in my previous career(s), I was able to address some of these endemic problems. As I learned how the system operated in so many interlocking and insidious ways, I could work with others in those fields to address the inequities.

I am almost ashamed to admit that it wasn’t until rather recently, however, that I realized just how harmful environmental policies have been. Among my previous colleagues, there was talk about limiting pollution and not overburdening communities, but the speakers rarely, if ever, meant Black and Brown communities. Yet, increasingly, the burdens of industry, transportation, waste management, and environmental degradation fell at the property lines of those communities.

I’m fighting for diversity and justice – and against systemic racism

Isn’t the persistence of these pervasive racist and classist attitudes and practices the reason why can’t we have nice things?

The belief that certain classes of people are better, more deserving of nice things, more entitled to freedom from the harmful effects of industrial processes and pollution – all is rooted in racism and classism of every form. Yet, it continues to be protected by and carried out through our major institutions and industries. It remains systemic.

And that is why I joined CLF.

I joined CLF to fight for nice things for all individuals and communities, especially people of color, Indigenous people, and other systemically disadvantaged people. The environment belongs to us all. As Heather McGhee describes it, we all live under the same sky. No one industry or people should have a monopoly on all nice things. That is what CLF fights for. I share that sense of purpose.

I know that working with CLF, I can leverage my experience and background in the fight for diversity, equity, inclusion, environmental justice – and against systemic racism. I want to help bring the voices of people of color to the table where they belong. Equally important, I want to help build and strengthen multiracial coalitions to fight against the fossil fuel industries that systemically pollute all our communities and sicken all our families. I especially want to fight against the political proclivities of those who think it’s okay to perpetuate such harm.

Environmental racism affects us all – and we all must fight against it

I joined CLF because I want to fight against policies that drive systemic and institutional racism. That fight is personal because we all want to belong, compete, and have nice things. But for the pervasiveness of race, racism – and I will add sexism, too – we all can achieve our individual strivings, live life to the best of our abilities, and have nice things.

Like you, I know environmental racism affects us all. We must work as hard to fight against it as we did against slavery, Jim Crow, segregation, and against those who think it is all okay today.

It is not okay.

We must learn as a people, The Sum of Us, to protect not only ourselves and the environment but also to fight against yet another form of systemic and institutional racism that is killing us all – environmental racism.

I joined CLF and my colleagues to be in this fight. And fight we shall.